Do you want to give a private company the ability to see inside your home on a regular basis, and store this footage on their servers? Do you want to give strangers access to your house? Do you want to risk invalidating your home insurance in case of theft? And do you want to pay $249.99 to do so when you could get all this for free? Then Amazon has the product for you…

Okay, so that might be somewhat sensationalist, but none of the points are entirely off base. Amazon recently announced the November 8th launch (in 37 cities across the US) of its latest stab at revolutionising the world of online shopping. Their latest product, Amazon Key, proposes a smart lock for the home which will allow Amazon couriers to unlock your front door via a one-time remote access code, deposit the package inside you home, and then lock your door again. All this being recorded by the Amazon Cloud Cam which comes as part of the package deal. You can watch live via the camera or choose to review the footage after the delivery has taken place. All this is available for Amazon Prime customers only.

It is also possible to use the smart lock to give friends and family one-off, recurring or permanent access to your home by generating special access codes for them. Amazon has also announced its plans to eventually extend this access to cleaners and pet sitters or baby sitters etc.

Home Security

In analysing the potential impact and trying to assess the future success of Amazon Key there’s only really one place to start: the issue of home security. The idea of giving a complete stranger the ability to unlock your front door is enough to make many feel queasy. Admittedly, Amazon couriers are subject to background checks, and the camera recording footage and uploading it to Amazon servers, with Amazon knowing who is meant to be delivering the package should make it relatively easy for Amazon to identify potential thieves. Nevertheless, how stringent these background checks are we don’t know, and all this hasn’t stopped Amazon delivery drivers from routine thefts before, so who’s to say that this wouldn’t occur with Amazon Key?

The potential issues with home security by no means rest with the potential for theft from delivery drivers though. Hacking of Amazon’s new smart locks must be entertained as a possibility. Whilst this point applies to smart locks more generally and the likelihood of it occurring is surely remote at best, it is by no means impossible. By opening your home to Amazon you also open it to the possibility of cyber attacks in the future.

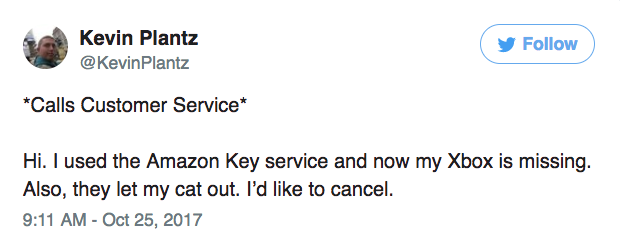

Amazon’s biggest challenge with this latest venture will be to overcome social norms, the concept of letting a stranger into one’s home unattended is quite simply an alien concept for most and demand for the Amazon Key will undoubtedly take time to gather as the idea tackles the obstacle of getting a foothold in society. The evidence thus far isn’t exactly in favour of the idea, countless tweets, like the one below, and comments on news articles voice their concerns. Whilst this clearly isn’t exactly how the Amazon Key will operate, it’s these kind of social fears that it will have to overcome in order to have success, and this is perhaps the biggest challenge facing the product.

The Competition

Among other threats to the product are, of course, all the alternatives which can act as substitutes. As mentioned earlier the combination of the Cloud Cam and the Key cost a total of $249.99, what Amazon have to ask themselves is whether there’s a market for the service at this price. Now, the benefit to the consumer is simply that the product arrives inside their home at any time of day, whether they be present at home or not, safe in the knowledge that the package won’t be stolen from their safe place. The question is how prevalent is package theft in society and how much of an inconvenience is it to the consumer.

Many articles report how package theft constitutes a growing issue, yet there is very little reliable data on the matter. Even then, for the majority of consumers who don’t purchase high value items from Amazon the value of any theft is highly unlikely to amount to anything near the $250 cost. Plus the fact that in the case of many thefts customers are able to claim back and work with Amazon to claim back on their purchase.

This point aside, there are many other ways that customers of Amazon can assure that their packages are stolen if they feel uncomfortable having products left in a safe location. A lock box would do the trick, leaving a key for the courier and then having them put the package inside, lock the box and post the key through the letterbox afterwards. All this for considerably less than the price at which Amazon offers its smart lock.

Other companies also offer smart locks at considerably lower prices, a quick google search for smart locks brought up locks from companies already established in the lock market, such as Yale, offering smart locks for less than £100. Can Amazon realistically compete in this market given the cost of its product?

Intrusion

Alongside this, the feelings of privacy in one’s own home may be cause for concern, with filming undertaken on the Cloud Cam being uploaded to Amazon’s servers. Yes these servers are secure to a high degree and the camera only has to be on whilst the parcel is being delivered, again Amazon will have to overcome the social reprehension regarding the inside of their homes being filmed and put onto Amazon’s servers. This has been a concern raised by many online since the launch of the product was announced.

Insurance

Questions also have to be raised about how insurance companies will react in the face of Amazon’s new idea. If theft occurs in the case of an Amazon delivery where you provide access to your house via code, will the insurance company cover this? This kind of uncertainty adds to the mountain that Amazon has to overcome to have success in the market.

Do I think that the Amazon Key will find success in the market? No. I just can’t see where the mainstream demand for the product will come from given the alternatives, such as lock boxes, and the fact that package theft for most isn’t too serious of an issue given that parcels can be left in a safe place or with a neighbour. Then there’s the almighty issue of the social norms and intrusiveness which Amazon must overcome to have success with the product. Yes there’s the potential for all this to change and smart locks may well become commonplace, but it’ll take a whole lot of time and effort to reverse. Thirdly Amazon is restricting it’s market by making the product only available to Prime customers. Granted most people considering purchasing a smart lock from Amazon will be those who buy from them regularly and already be Prime customers, but still it restricts their market somewhat.

All this being said, this move from Amazon is probably the right one strategically, no other company has made a move into this market before, and if it does take off Amazon only stands to benefit from first mover advantage. Further, Amazon can afford to take a loss on the product without it hurting the business in a meaningful way. In my article examining Jeff Bezos’ business strategy, I wrote about his desire to keep ahead of the game. This is a huge part of it, investing in products which could innovate and hit it big, even if they probably won’t.

This higher interest rate increases the opportunity cost of consumption and investment having a deflationary impact, which caused prices to fall by 25% in the US (1929-1933) Crafts and Fearon (2013). This was worsened by the fact wages were downward rigid, thus the price fall pushed real wages up causing mass unemployment, peaking at 24.75% in the US (1933) (Source: u-s-history.com). Such figures indicate the seriously detrimental impact that deflation can have upon an economy, this is where the lesson lies: an independent monetary policy, and willingness to use it would have allowed governments to devaluate the currency via monetary expansion in case of balance of payments deficits until parity was restored thus reducing deflation and unemployment risks. However, ‘Monetary and fiscal policies were used to defend the gold standard and not to arrest declining output and rising unemployment’ Crafts and Fearon (2013). The Fed raised interest rates in 1931 and 1932 which prolonged the recession and transformed it into the Great Depression.

This higher interest rate increases the opportunity cost of consumption and investment having a deflationary impact, which caused prices to fall by 25% in the US (1929-1933) Crafts and Fearon (2013). This was worsened by the fact wages were downward rigid, thus the price fall pushed real wages up causing mass unemployment, peaking at 24.75% in the US (1933) (Source: u-s-history.com). Such figures indicate the seriously detrimental impact that deflation can have upon an economy, this is where the lesson lies: an independent monetary policy, and willingness to use it would have allowed governments to devaluate the currency via monetary expansion in case of balance of payments deficits until parity was restored thus reducing deflation and unemployment risks. However, ‘Monetary and fiscal policies were used to defend the gold standard and not to arrest declining output and rising unemployment’ Crafts and Fearon (2013). The Fed raised interest rates in 1931 and 1932 which prolonged the recession and transformed it into the Great Depression. This was thanks largely to the actions taken by policymakers. There are two key points to be made when reviewing the actions taken: firstly, expansionary monetary and fiscal policies were undertaken on a large scale to stimulate the economies, something crucially missing during the Great Depression; secondly these actions were taken quickly and confidently which prevented deflationary expectations from setting in long term and maintained confidence on the part of economic agents that the situation would improve. After the start of the Great Recession both the Fed and Bank of England (BoE) cut interest rates heavily with the US going to 0% and the BoE heading to its lowest rate since 1694 by the end of 2008, even with these interest rates being near the zero lower bound it was very important for ensuring that deflationary expectations didn’t set in upon the economy, here it is clear lessons were learned from the Great Depression.

This was thanks largely to the actions taken by policymakers. There are two key points to be made when reviewing the actions taken: firstly, expansionary monetary and fiscal policies were undertaken on a large scale to stimulate the economies, something crucially missing during the Great Depression; secondly these actions were taken quickly and confidently which prevented deflationary expectations from setting in long term and maintained confidence on the part of economic agents that the situation would improve. After the start of the Great Recession both the Fed and Bank of England (BoE) cut interest rates heavily with the US going to 0% and the BoE heading to its lowest rate since 1694 by the end of 2008, even with these interest rates being near the zero lower bound it was very important for ensuring that deflationary expectations didn’t set in upon the economy, here it is clear lessons were learned from the Great Depression.

![IMG_20170816_223458_531[1]](https://jceconomicsblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_20170816_223458_5311.jpg?w=840)